Hello, friends! This episode of Loitering features an interview with the one and only Vidur Malik. Please listen and follow along below.

Sonia Paul 00:13

Hello, everyone, welcome to Loitering, the occasional but lovable traveling mini pod I am currently testing in newsletter format. And today I am loitering over outside pho with a very special guest. Can you please introduce yourself?

Vidur Malik 00:30

My name is Victor Malik. I am a associate marriage and family therapist who lives in Hayward.

Sonia 00:36

And also, as you can hear, we are very much outside. We are in outdoor dining at a pho place in the bay. And, yeah, you can hear some children and families around us. But it's also a very special occasion because Vidur and I are catching up. And so, Vidur, the reason we know each other has to do with our time in journalism school together. So can you explain a little bit about your history as a journalist, and how that led you actually into an entirely different line of work?

Vidur 01:08

Yeah. So when I was growing up, I was trying to figure out what I was good at, and what I was passionate about. And I always knew I liked sports. And I always knew I like to write. So I thought, why not combine those two and become a sports writer. And I kind of took that kind of very naive idea through high school and college and worked on my school papers and studied journalism, and went to Columbia where I met you. And at that point, I thought that sports journalism was my calling. And I was just going to do it and not ask any questions about it. But as I got into the field and started working daily, as a journalist, I realized it just was not fulfilling for me. And I didn't feel like I could cut it as a journalist. I didn't think I had the qualities that somebody like you has or other reporters have.

Sonia 01:47

That's a lie

Vidur 01:47

It's not! Like, I didn't think that — you know, you have to be tenacious, you have to be okay, working unpredictable and long hours. And you have to be okay annoying people and asking questions that will upset people. And that always freaks me out. And I had to psych myself up every time I did an interview, or like, just went out and did reporting. And that was not sustainable. I couldn't do that into my 70s, you know, so I had to do something that I didn't dread doing every day. And I had always enjoyed mentoring and sort of just supporting people who are going through things. And I had done peer mentoring in high school and college. And I really liked the idea of just sitting with somebody, and not necessarily solving their problems, but helping them figure out a solution that works for them. And the more I thought about it, the more I was like, you know, you should be in some sort of counseling or psychology. And so I was living in New York, after finishing Columbia. And I wanted to go back home to California. And I applied to the Santa Clara University School of Counseling Psychology, and I got in, and I haven't looked back, and I work as an associate marriage and family therapist who is working on getting my license.

Sonia 02:50

Okay, that's quite a story. Also, I really want to unwrap more though, like the transferable skills between being a journalist and being a therapist. What do you see as some of the things that maybe you're taking away from actually being in journalism school that journalists themselves might underappreciate?

Vidur 03:11

Well, information gathering for one, knowing when to ask a follow-up question, knowing how to phrase questions to get a lot of information. That's a big one. And then the second one is just writing quickly. As a clinician, anybody will tell you who works in the field, there's a lot of paperwork, and a lot of documentation, and assessments and treatment plans. And often you're doing more paperwork than actual therapy. So being able to write quickly, and write clearly quickly is helpful for me, because I can write a note in a few minutes and kind of distill an hour-long therapy session into a few sentences and feel like I can do that pretty effectively. And journalism helped me a lot with that.

Sonia 03:48

Wow, did you feel like, self-conscious, though, about making a career switch? Because I think there are a lot of journalists who talk about like, 'oh, what would it be like to leave journalism,' but not even just with journalism, but with any industry — sometimes it's like seen as taboo, or it's just too daunting to actually make that switch. So what were — what were you thinking when you were actually going through this decision?

Vidur 04:11

I only feel self-conscious about it when I talk about it with other journalists. Because I think —

Sonia 04:16

— I hope not me,

Vidur 04:17

No. Because the worry is — they might think, well, Vidur couldn't cut it in this field. And I kind of think that too. Like, I felt like I was good at journalism, and I got generally good feedback. And I worked hard. But I just knew it wasn't sustainable for me. So I think some of the self-consciousness just comes through when I talk to people who are in the field and are probably gonna do it for a long time. And, you know, sometimes they feel like, oh, I don't measure up to them. But, you know, I work through that. And it doesn't stop me from telling people what I'm doing now. So that's really the only time I get self-conscious about it.

Sonia 04:48

That's so interesting, but like in terms of measuring up, you're actually like doing a really great thing right now. Like, I mean, being a counselor, especially in this era that we're in right now. So can you talk a little bit more about the work you're doing? You're working with high school students, right?

Vidur 05:04

Yeah, I'm a clinician at a high school in the Bay Area. So right now we're doing virtual learning. So logistically, that just presents a challenge in terms of how do you do the work over a computer or over the phone. It's work that has always been done, you know, with two people in the same room, and kind of that, that feedback that you get from being in the same room with somebody that's nonverbal, that you can't quite like quantify. And that kind of doesn't really exist over the phone or over a laptop, but you just find ways to get around it. And I think now more than ever, people just need space to check in about themselves. So even if it's done remotely, or virtually, the space itself is still important.

Sonia 05:45

I mean, I can't imagine — well, I can a little bit because I have some friends who are teachers — but what it's like to be a high school student and learn in a pandemic. Can you talk a bit broadly, like while respecting patient confidentiality, about some of the issues that young people are going through that maybe we might take for granted as adults or working professionals going through our own hurdles?

Vidur 06:07

Yeah. I think that generally, such a big part of school, and education, is just socializing with peers and understanding just how to interact with people your own age, how to have conversations, how to make friends, how to handle conflicts, and resolve them. And that's a lot harder to do when you're not in school every day with your classmates in a class. So I think that social element of school that we all probably took for granted, I know I took for granted, just doesn't exist anymore. The idea of like, being with the same classmates, maybe throughout K through 12, being with the same classmates in the same class every day, that just doesn't exist. So I think that social element is missing. And I think, you know, I wonder what it's like for our students to go through that. I also think that in terms of the education itself, you know, it's a lot easier to get distracted, when you're at your home environment in front of your laptop, as opposed to when you're in school, you kind of know, I'm in school mode, right now, when I can get home, I could play PlayStation or do anything else I do at home. But now, all those distractions are right there in front of you. And it's hard to get away from them when you don't actually leave your house. So that's a huge issue that I think a lot of students are facing right now is just, there's no boundaries between home and school. That doesn't really exist right now.

Sonia 07:20

Yeah, it's like a sort of lead up to... there's no boundaries between work and personal life for a lot of working professionals. Um, how do you advise your students to cope? I mean, you can't necessarily give a solution to their problems, but you could advise them on how they can work toward a solution. So, how are you doing that?

Vidur 07:43

So I think — I try to support my students with a lot of mindfulness nowadays, I think has been helpful. So you know, if they find themselves getting distracted, while they're in class, having a point of focus in their room, whether it's like a poster or a post-it note or a picture that they can use to kind of reset themselves and just get back into the moment can be helpful. So I'll recommend a lot of like quick mindfulness activities that a student can do, no matter where they are kind of at anytime. I think in addition to that, just taking breaks. So, really just utilizing those breaks, to just go for a walk, get some food, just whatever they need to do to kind of safely cope with getting through the school day is helpful. So I think those two things are things that I recommend, and then just again, having this space where they're like they're meeting with me once a week to check in, you know, just to know that whatever they're carrying, that they do have a place to get it out whether it's with me or another trusted adult or a friend.

Sonia 08:33

Right. So in addition to doing this work, you're also working part-time on the weekend, counseling adults. So from an outside perspective, it seems like you're surrounded by a lot of people who may just like be venting to you, or you're listening to a lot of difficulty that people are encountering and trying to help them manage that. But also, like how are you managing your own stress and mental health at this time, I think especially like, we were talking about vicarious trauma, sometimes we can be too empathetic, or too empathic. So how do you think about taking care of yourself while also helping people take care of themselves?

Vidur 09:12

So I've always been somebody that likes taking little breaks, I'm not somebody who could like work several hours without a break. I was never like that at school either. I never pulled all nighters or anything like that. So, I really prioritize taking small breaks, even if it's just going for a quick walk around the neighborhood. I do that, you know, I'll watch TV for a few minutes if I'm in between like phone calls or meetings. So wherever I can, I try to just do something fun and something safe for myself. I also am in my own therapy, and that's a great place for me to kind of have an outlet to talk about things. I think what I found is really important is that when I'm with a client, I have to be fully present for them. So that means that stuff, you know, it'll come up because I'm a human, and I'm gonna have reactions to things that my clients say. But I know that that's not the time for me to get that feeling out. So for me that time is therapy. So I know that I have that for me. And that allows me to just be fully present, when I know that it's not my time to talk about my stuff, because I know that I do have an opportunity for that. So that's reassuring to know that that opportunity does exist for me to have that space.

Sonia 10:11

And how would you...um. How would you advise friends who are maybe in the position of being kind of pseudo-therapists to their own friends? I think cuz, you know, people like to take care of each other, we'd like to be available for support. Sometimes people do need feedback outside of therapist they may already have, but also like, what happens when maybe friends may project their own feelings or insecurities, or also, just maybe trying to problem solve too much when they really shouldn't be in that position? So how do we think about being available as friends for each other, especially right now, versus knowing what boundaries we should actually establish around that?

Vidur 10:53

Yeah, so I think support is so unique for everybody. And it looks different for everyone, depending on what they're going through. So I think one thing that could be helpful is when you are being a friend to somebody and supporting them through something is asking them what they need. So you may even ask, like, would it be helpful if I gave advice, or like, talked about what I think would work? Or do you just need me to listen right now? Do you not need advice? Do you just need space to talk? So, knowing what your friend needs in the moment is a great way for you to think about, like, how can I be helpful right now without kind of taking on too much, you know. If somebody doesn't want a problem solver, and you do problem solve, I can, you know, lead to some awkwardness, and it can lead to you taking on too much responsibility. So, asking at the beginning, you know, how can I be helpful to you, it just allows you to kind of understand, like, what you can do in the moment. And I think that prevents that sort of vicarious stress and allows you to just be fully present in the moment with your friend.

Sonia 11:45

Wow, that's so interesting. Thank you so much, Vidur. And as you could tell, like, our own environment has changed the family next door to us with the very active child — actually, they're still next to us. But the child is now slurping his pho. But yeah, is there anything else you want to add, Vidur, that we didn't touch on?

Vidur 12:04

Um, I think just, you know, not that I have all the answers or anything. But I think one thing that I've learned for myself is that it's hard sometimes to measure how much we're carrying or how much stress we're facing. And I think right now is one of those times. I think that we are all dealing with the effects of the pandemic, and the fires and just what's happening in our country, in our world right now. And I think it might be helpful every now and then just to say, how do I notice myself carrying stress? Is it in my body, is it in my shoulders, is it in my chest, do I get headaches? And just take a moment to say, what could be helpful for me right now? Can I take a walk? Could I take a nap, can I listen to some music. And if you do that a couple of times a day or a few times a day. Again, it might not solve what's going on for you. But it will give you a chance to just be kind to you and kind of put you first in a really intentional way. Because I think sometimes it can be easy to put us, you know, kind of down the list of priorities. So just checking in with yourself regularly every day just allows you to kind of make you number one for a little while, and just sort of respond immediately and safely to ways that you might be carrying stress.

Sonia 13:16

Thank you so much, Vidur. You know what, maybe you're not a journalist anymore, but you can be like a podcast host about these issues.

Vidur 13:23

Thank you. I will think about that.

Sonia 13:25

We can have an updated Loitering episode. Okay, so that's all we have for today of Loitering, the occasional but lovable traveling mini pod I am currently testing in newsletter format. Thank you for listening and have a nice day. Goodbye!

*Outside pho = outdoor dining with safe social distance. Vidur ate pho, while I had boba (I had actually eaten a Vietnamese sandwich just before!)

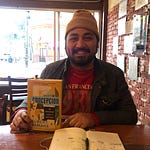

Speaking of food, this is me not trying to be a “journalist influencer” but a “Sonia influencer,” and this is pretty good.

Some links:

Speaking of young people, this story is a grim but necessary read on the students left behind by remote learning.

If you, like me, are an alum of Columbia Journalism School (or are a current student, faculty, or staff), please consider signing this petition to drop the criminal charges filed against Andrea Sahouri. Sahouri is a reporter for The Des Moines Register and was arrested back in May while covering a protest against the killing of George Floyd. While other journalists were arrested covering protests over the summer in various cities, the charges were usually dropped once a journalist’s identity was established. Sahouri is one of few journalists still facing criminal charges.

“In the last three months America has lost more people than Sri Lanka lost in 30 years of civil war.” And more here on what it means to experience collapse.

If you’re interested in China, TikTok, balkanized internets, and what it’s like to try to practice journalism when a government doesn’t like your reporting, have a listen to this interview on Big Technology with BuzzFeed’s Megha Rajagopalan. You can read a discussion of that interview here too.

Around the same time COVID-19 was breaking out in the U.S., I was anticipating traveling to Detroit to report a story for the podcast 70 Million that I first started researching at the end of last year. Little did I know that the issues at stake in the story — police-mandated surveillance and facial recognition technology — would animate on tensions that would erupt even more as the year moved forward, and we entered into a national conversation on policing in our country. Given the curtails to travel the pandemic imposed, I ended up not reporting on location in Detroit, but doing a very meta thing: I recorded a FaceTime tour of downtown Detroit, and a Zoom tour of the police department's "Real Time Crime Center, as part of my reporting about the rise of cameras all around us. The pandemic has definitely made all of us way more comfortable in front of screens than ever, but it's worth thinking about what happens when this comfort — and the fine lines between real safety and the perception of safety — also contribute to the rise of surveillance. Hope you'll have a listen to the story.

And on a final note: Let’s all become hot for ourselves and not care so much who does and does not see it in quarantine.

I’d love feedback, or just to hear from you, so please feel free to get in touch. And if you know someone you think may like to read or listen to Loitering, please share. Thanks.

Share this post