Dear Friends,

It’s no doubt these are hectic and stressful times. At the end of the newsletter, I’ve linked to a few resources that may be useful for you and your families and friends as we all work to help curb the spread of COVID-19.

Wishing you all good health, good vibes, patience and lots of support!

XOXO

Sonia Paul 00:10

Yeah, what happened to your leg?

Sopan Deb 00:12

Oh man, I wish there was a better story behind this but literally I was crossing the street in the Lower East Side and I got trucked by car. I wish there was a better story, like, I was like, saving a baby from getting run over or something, but I think what happened was I didn't realize it was a two-way street. I looked one way, didn't see cars coming, went for it, and then got trucked from the other side.

Sonia 00:32

Trucked from the other side meaning a truck—

Sopan 00:34

No, sorry, a car hit me. A car hit me. If I truck hit me, I don't think I'd be here right now.

Sonia 00:39

Oh my gosh, did you need surgery or anything, what happened?

Sopan 00:42

Yeah, I had surgery the next day. There's like, a rod inside my leg that will always be there. Like a permanent friend. But you know, all things considered, you know, there's no ligament damage or anything. So, it's not so bad.

Sonia 00:53

You seem awfully easygoing, given the severity of what happened.

Sopan 00:58

Well, I'll answer seriously because I know you're sound-checking. I also realized that I come from a huge privilege here because I have a kind of job that allows me to work from home. There's that. Wesley, who's my fiance — Wesley has the kind of job where they let her stay at home for a month and take care of me. And so I had that. I have health insurance. So, like, it could have been a lot worse. I'm also fortunate in the fact I got hit by a car and lived, right? It could have been a lot worse. It's annoying and painful in the meantime, but it could have been a lot worse. That's what I keep telling myself.

Sonia 01:31

Yeah, that's a nice way of framing it.

Sopan 01:34

Yeah, otherwise just gonna be sad all day and no one wants to do that.

Sonia 01:37

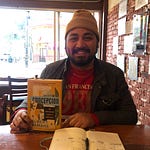

Totally. Okay, let's backtrack. Hello, everyone. Welcome to Loitering, the occasional but lovable traveling mini pod I am currently testing in newsletter format. And today, I am loitering over doughnuts with a very special guest. Could you introduce yourself? Who are you and what do you do? What is this job you have that gives you a certain amount of privilege and flexibility?

Sopan 02:00

Yeah, sure. So my name is Sopan Deb. I am a writer for The New York Times where I cover mostly the NBA now, but I also, I recently left the culture beat of the Times. And the culture is like film, TV, television, dance, art, music, and I still contribute to that section. But most of my job is covering basketball now. Then before that, I covered the presidential campaign for CBS. I covered the Trump campaign, I was one five or so campaign embeds that traveled the country with him for a year and a half. And then I'm also a comedian on the side. So, I have a bunch of different balls in the air.

Sonia 02:08

And now okay, so you recently wrote this book called Missed Translations: Meeting the Immigrant Parents Who Raised Me. And we got in touch because I saw that you had posted some excerpts of what you had sent to publishers about why you wrote this book. So can you talk a little bit about the motivations behind this piece of work?

Sopan 02:47

Yeah, absolutely. So the book is about how essentially stand up comedy and covering the Trump campaign pushed me to reconnect with my parents. My parents were arranged to get married. They're both Indian. They're both Bengali. And they had a very bad marriage. And so when we were growing up, I didn't know anything about them. We were more like distant roommates than we were a family. We barely ate together. When we did talk, it was just yelling at each other. So I grew up never getting to know them. I didn't know how they met, I didn't know how many siblings they had, and I didn't really know any of my grandparents. And what that did is it made me want to be white. I grew up in a mostly white suburb of New Jersey called Howell. And I'd go to my friend's houses. And I'd see them eating dinner together and having normal conversations with each other, talking about crushes and talking about therapy and stuff like that, and be like, wow, I don't have that in my house.

And then, in college, my father after my parents finally got divorced, my father just left the country and moved back to India without telling anybody. Just bounced. Um, and then my mom and I kind of lost touch. And then, as I was turning 30, I realized it had been more than 11 years since I'd seen my father and it had been several years since I'd seen my mother. I didn't even know where they were living at the time. It was time to go find them, and time to go reconnect with them, and actually learn who they are, and what their stories are. And so I did, and that's what the book tracks. I found out a lot of stuff. There are a lot of plot twists throughout. There's a lot of like, crazy stuff that I found out that was really shocking. But when I started this process, I literally did not know where they were living. I didn't know their ages.

Sonia 04:20

Yeah. So like, when you were growing up, I mean, you mentioned it felt like you were more like distant roommates. But, I felt like in the beginning parts of the book, it did feel like there was a sort of sense of culture or family understanding that they were trying to embark on you. You talk about like, you were a musician, and you used to practice Indian music. So what happened?

Sopan 04:41

Yeah, I don't know if you can relate to this. I'm sure you can on some level. I think a lot of South Asian families, what they do is they put their kid in activities, but it's for the resume. It's not for themselves. It's not like my parents put me into piano lessons because they were excited to nurture my mind. They wanted me to do better on my SAT scores, and, you know, being a musician helps with that, right? So when we were growing up, we had a little bit more of a family culture. It was strained. It got to a point where it was intolerable as I got older. But when I was younger, yeah. You know, my mom put me in piano lessons, karate, baseball, all the regular stuff. But, I always felt like it was more for her than it was for me. And I think that's not necessarily unusual with immigrant children. And then by the time I think I kind of got to middle school, that's when everything kind of started disintegrating to a point where any semblance of family culture we had was no longer in existence.

Sonia 05:34

Yeah. And wanted to get into the beginning of your book, because you — you talk about being at the Big Brown Comedy Hour.

Sopan 05:42

Yeah!

Sonia 05:43

Yeah! And, okay, so there are a few passages that I thought were really telling and I wanted to like, kind of explore a little bit more sort of the truth that you were getting at. I don't know if you would prefer I read or if you want to read it yourself? Okay. All right. So—

Sopan 05:59

I've read the book, so I know—

Sonia 06:02

I've also read the book, I read it over the holidays. So, you're at this like Big Brown Comedy Hour, you talk about like, being a stand up comic. And you're saying that you know, talking about your family and background. And so you get in here, you say, "But I was handling this crowd someone else's honesty with that joke, telling them what I pictured a stereotypical Christmas with Indian parents to be like." And then you note, "It was a paradox. I had spent much of my life running away from my skin color and culture. And yet the thing I felt most comfortable discussing on stage was my South Asian identity. Talking about any version of the brown experience felt cathartic, whether it was the mangled one of my childhood, or the way I imagined a happy brown kid growing up."

And then on the second page right after that, you note, "But what the crowd never knew and what I couldn't bring myself to tell them was the crippling anxiety and sadness I felt about each the truths I had morphed into a laugh line. I was comfortable talking about this stuff from behind a microphone, but only to an extent. Sometimes it felt like I was playing the part of a brown guy on stage. But when I dropped the facade and delved into my actual life, the words deflected the guilt and vulnerability I wasn't yet ready to face. Much of my material, especially the stuff about my parents, resulted from unfamiliarity, both with myself and with them."

And so, like, I really wanted to explore this tension you talk about of being a "version" of the brown experience, or playing the part of a brown guy on stage. And so I'm like wondering, was there a particular example or role model of that version of brownness that you were trying to attach yourself to? And if so, who was that? What was that?

Sopan 07:48

Was there a particular role model?… You know, speaking about stand up. When I first started doing stand up, I tried to be very much like, in kind of the Mitch Hedberg type, doing observational comedy. I remember the first joke I ever told on stage was, "Oh, I like to say a word about race relations. Has anyone here ever had sex while watching NASCAR? If not, then we can't really talk about it." And I remember this just, just total silence from the crowd. And it was a lot of like, those types of kind of one-liners. I was like, wow, I'm bombing with this. So suddenly I start talking about being brown. The problem we talking about being brown is that I spent much of my life, as you just read, feeling white on the inside. Not wanting to be brown, because my thought was being brown was what brought my parents together. They are miserable. They have made me miserable for much of my life. So, I'm not going to subscribe to being brown. I'm gonna identify with my white friends and the white people around me because they seem happier.

08:46

And then as I started doing stand up, I found myself oddly wanting to talk about being brown. And I would do that one of two ways. I'd either talk about the true stuff, which is — “funny story about my parents.” Or I'd make stuff up. You know, and like one of the jokes I told was about Christmas. And this is the one you just mentioned. And the joke was something like, "One of my favorite traditions of Christmas is asking my mother what the meaning of Christmas is. And she'd said, 'oh, it's when Jesus died on the cross. Well, Mom, well, why did Jesus die on the cross? It's because Jesus decided become a carpenter instead of a doctor." And, and I love the joke. It always kills. You know, whenever I tell the joke. And I still tell it because I really like the joke. But it's dishonest. Because I never had a Christmas with my parents growing up. We never did presents. I was delivering what I assumed other brown kids were doing with their families in writing that joke. But I felt oddly comfortable doing it.

So it got to a point after, you know, six, seven years of doing stand up where I was like, why is this what you want to talk about? Is it possible that you're actually way more interested in kind of the brown side of you? And it's not a side, it's who I am. Is it possible that this is actually what you subscribe to and that you want to connect with that side of yourself? And that's essentially how I thought of, okay, well, maybe it's time to get in touch with your parents. Maybe now is the time.

Sonia 10:06

Yeah. It's so interesting, because I'm wondering like, was there something fueling the assumption you had about what other brown kids or South Asian kids did? Like, where did the notion that this would be what they did come from, you think?

Sopan 10:21

Well, the notion came from the fact that not every kid had parents that were as disconnected as mine were. So you have to assume that they're connected somewhere. And if they're connected, they're probably celebrating Christmas, they're happy somewhere, they're happy in some way. And so I pictured what that happiness would look like in a typical brown family. And I say typical, I mean, it's by no means monolithic. There's many, many different stories, different variations. But in my case, it was just assumptions. I'm not saying that they were correct assumptions. But I was making up a composite in my mind of what a happy life for me would have looked like, if I had the traditional kind of, "son of an immigrant parents" experience.

Sonia 11:04

Interesting. And, you have a brother.

Sopan 11:07

I do.

Sonia 11:07

An older brother. How much older is he again?

Sopan 11:09

10 years older.

Sonia 11:10

So, was there any discussion between the two of you growing up about what your experiences were like? Was there any sense of sort of bonding because you were both growing up in this experience? Or was it just like, the age difference was too much, or—

Sopan 11:25

Very little discussion about it — for several reasons. The first of which, I mean, look, the age difference matters. Let me tell you how that manifested itself. So when I was eight, he was going to college. When I was going to college, he was just getting engaged to get married. When I was at the age that he was getting engaged to get married, he just had a second kid. So we've never been on the same page, even just like on a life, world. We have a perfectly good relationship, but he was out of the house for a lot of the bad times to my parents. And he had a different experience with him than I did. He's not in the book as much, not because I didn't want it to be, but because this is my story. And it's not his. He would have a different story to tell.

So, part of the thing I write about in this book, and why I think this book has appealed to a lot of people is that, you know, it's about communication. It's about how important it is for families to communicate. And my parents never did. And that's why we ended up having the relationship, or lack thereof, that we did. We never communicated, we never tried to talk to each other. And the thing you just mentioned about, did you and your brother talk? Well, we didn't, really. And that's one example of where I think our family had a lot of shortcomings. And that's not just on them. It's also on me for not giving them a chance.

Sonia 12:39

Yeah, it seems like that’s something that you sort of realized through the course of trying to discover your parents, is that you had certain expectations for what their parenting ought to look like. But then it was only recently that you sort of started to examine, well, what does it mean to be a child, and sort of respond to my parents in a certain way, because you know, you talk about, like, therapy and the importance of communication. And so what was part of the process of you coming to realize those aspects of yourself that were sort of lacking along the way? Did it have to do with kind of just like, growing up and reflecting, or was therapy a part of that? Like, was it just a part of the communication your parents eventually gave you?

Sopan 13:20

Well, I'm older now. And I'm much more settled now. Right? I have a job, I have a career. I know where my next paycheck is coming from. So I kind of, I think I have mental space right now to think about that stuff. Something like this requires everyone to look inward. And people can do that to varying degrees. I think a lot of people have a tendency to say, "This thing is happening to me, this terrible thing is happening to me. This coworker is mistreating me. This boss is screwing me over. This friend is being really rude to me. This person did this to me." And we rarely ever look at what we are contributing to that. What is it that you're contributing to the dynamic that is making the final product what it is? And I realized, as I got to know my parents and speak to them and hear their stories, and listen to how they got to where they are, and why my father left the country, and how my mom ended up in New Jersey, I realized like, 50 years ago, your mom and dad, this isn't the life they pictured for themselves. They didn't get here by themselves. They got here in part because of several factors. But you can't discount the fact that you, as a child, are a part of that. And does that mean that I take like, full responsibility, no, I mean, as I said, we have to look inward. That means all of us have to look at what we contributed to that. But people have varying levels of capability to do that. And I don't know what my capability is. But throughout the book, I think it increased, if that makes sense.

Sonia 14:46

Yeah, no, it's really interesting because you talk about reaching out to your parents and going to India to meet your father, reaching back out to your mom. You noted that a lot of it had to do with you had turned 30. You were thinking about this, but also, you talk about your career and like, being a campaign embed with Trump. And I'm just wondering, was there a specific moment, a sort of like, turning point that you really realized, no, now is the time I need to reach out to my parents?

Sopan 15:17

I got a wedding invitation to go to India for an old friend of mine. She was getting married, and she invited me to her wedding. And so I looked at my then-girlfriend, Wesley, who's now my fiance, and I said, "Oh, do you want to go to India?" And I was always nervous about going to India, like, because it's a lot of time off work, and, you know, whatever. And then, you know, I was like, well, we're going to India, you know, my dad's out there. I don't think I could justify going to India and not see my father. And then, you know, Wesley, who's, you know, kind of the star of the book and in her own way, she said, "Of course, you have to go. We have to go." And then I said, "Well, if I'm gonna find my father, I can't not find my mother as well." And so I decided to find my mother.

And then after that, I was like, whenever in my 20s and growing up, whenever I tell other people about my parents and my relationship with them, or my dad leaving the country or that I haven't spoken to my mom in years, I never thought of it as an abnormal thing. It's just what I was used to. In the same way that, if you had a college roommate that you're no longer in touch with, that's normal. That's not an abnormal thing. That's how I felt about my family. But whenever I tell other people about it, they said, "That's not normal." So, I was like, since that's not normal, we might as well track this process in some way. We might as well write down how I'm feeling every step of the way. We might as well journal it in some way. I mean, you are a writer. I mean, this is what you do for a living, you might as well do that.

Initially, we thought about doing it as a documentary.

Sonia 16:36

Who's we?

Sopan 16:36

Me and Wesley. My now-fiance. But at the time, she was my girlfriend, and so we, we kicked around doing it as a documentary, but I thought putting cameras in my parents' faces would have been a little bit too invasive. Given how, you know, they're not very media savvy. It would have been a lot for them, I think. So I think writing was the more — easier way to do it. So throughout the whole process, I'm recording, I'm shooting video, I'm writing, and so a lot of the reactions you see in the book are in real-time, very exact, and they change throughout the book. A lot of memoirs are like, based on recall. This book, we're calling it a memoir, because it's easy to call it memoir — it's not really a memoir. It's more, like, narrative nonfiction in that very little of this is based on recall, it's based on recordings, I've spaced on my notes in the moment and all that stuff. I think to help ease my communication with my parents, I approached it like a journalist. Dispassionate, let's see where this takes me. Because that took a while before I was like, really comfortable with my parents. And really comfortable in talking to them about stuff. Because look, you're South Asian, you know, that we're not great at talking about stuff at home. You know, we're not.

Sonia 16:39

Unless we just want to like, vomit it all out.

Sopan 17:44

You know, it's true. Like, you know, there's no like, we're not good at talking about feelings. You know, we're not good at healthy confrontation. Because the generation before us, my parents, when they came to this country, they didn't have the freedom to think about mental health. And they didn't have the freedom to think about feelings. They were just trying to get through the day. They're just trying to figure out how to get to bed at night, and where the next paycheck was coming from. You know, my dad has a story about coming to this country with $8 in his pocket. Every single Indian dad or uncle has that same story. And it varies how much money they have in their pocket, but it's usually less than $20, is usually the range. But whether that's accurate or not, it speaks to kind of a survivalist mentality.

And so I grew up in white America, in the suburbs, where my fulfillment is emotional, it's physical. I'm striving for — how do I pursue my professional passions, but also my creative passions. My parents never thought about pursuing passions. They never had that option. They didn't even know to have that option. It's not like people that pursue an acting career, but don't make it. It's my parents wouldn't even know that they could pursue an acting career. And so it made those conversations really interesting, but I had to approach it as a journalist first just for my own — my own comfort level,

Sonia 19:01

What's really striking to me is that this book is like, intensely personal. And, I mean, it's trying to uncover a lot of uncomfortable truths about not just your life, but your parents' lives. And so, how was it for you to get your parents on board with that? I mean, I feel like a lot of the sort of shield about the discomfort surrounding their lives has to do with shame and what they want other people to know about them. And so here you go, let me like, broadcast it to the world in a published memoir, and like, do they realize that there's going to be an audience getting to know them in this intimate way now? Or was it more just like you think they were so excited to get to meet you again?

Sopan 19:38

I think it was that. I think it was getting to see me again. I think they had both reached a point in their lives where they did not think they were going to see me again. Or they didn't know. And frankly, I didn't either. I won't delve too much into this other than to say, reading the manuscript for them was difficult. But, look, I made clear to them from the start what I was doing. I was very open with them and transparent with them about the process. And they reacted differently to the book. But they both had their issues with it. And honestly, if my mom wrote a book, and my dad wrote a book, and my brother wrote a book. If they wrote, each wrote their own versions of Missed Translations, it'd be much different than mine. All I can say is that this is my version. This is my truth. This is what I can bring. I don't think I would have done anything differently.

Sopan 19:39

And I guess I'm wondering, did you have certain goals or expectations of what you wanted to find out from your parents? Or was it kind of like, let's just see where this goes?

Sopan

You're starting from zero. There's some stuff I found out that I was genuinely shocked by. One of the first questions I asked each of my parents was, what's your birthday? Because I didn't know!

Sonia 20:41

Yeah, I was just about to ask like, so did you celebrate your birthday growing up?

Sopan 20:46

Every now and then. Rarely.

Sonia 20:48

But it's just like, this idea. It's like, you have a birthday. Your brother has a birthday. Did you ever wonder, do my parents have a birthday? Why don't we blow out candles for them?

Sopan 20:55

No, I, I, we —I didn't. It's very strange, right? You know, I'd celebrate my brother's birthday or vice versa. I never once thought about my parents' birthdays were. Because we were just that distant from each other. You know, I'd see my friends be close with their grandparents. I never once thought about, okay, who are my grandparents? I just never thought like that. It was very strange. It's still very strange. I never thought to ask, like, did you have brothers and sisters growing up? I mean, I knew one uncle. But even just how they met. I never knew that story.

So, to answer your question, there are two things that I did know I want to get at. The first of which is, I wanted to know why my father left this country without telling anybody, because I think I was deep down very hurt by that. Secondly, there was a period of time when my mom was so depressed when I was in middle school, that she essentially just locked herself in her room for about, I want to say it was about, six months. And she'd only come out to like, go to her job, which was as a cashier at a Drug Fair, which is now Walgreens. I was 14, 13-14 years old at a time, and I never understood what was happening. And I wanted to know from her, what was that? That was a little bit strange for a 13-year-old to watch, and like not see his or her mother for a while.

22:05

And it was only in talking to her now that I understood the depths of depression she was dealing with. And it was only in talking to my father, that I understood the depths of depression that he was dealing with, and the disconnect that they both felt from us, as children, and the world around them. And so those were the two things I really wanted to get at. Everything else was just, where are we going from here? And part of it was also, I wanted to confront them and tell them look, you guys made me really unhappy as a child. And why did that happen? You know, and to varying degrees, you know, my parents were able to look inward. And now, as a result, I view them as humans in a way that I didn't before. I don't mean like, I didn't know they were humans. I mean, like, they're more than distant footnotes from my past. They're people in my life, if that makes sense. I keep saying if that makes sense. I'm sorry.

Sonia 22:56

No, no, it does make sense. I think it's really interesting because, you know, one thing I really appreciated about your book is that it really gets into a version of an Indian American childhood that isn't really public. I think like, what I was so interested is that like, there's this performance of brown identity that people who get to be spokespeople for the quote-unquote community or the diaspora talk about, and they sort of talk about growing up with a sense of Indianness in a way that almost seems very nostalgic, and like, rooted in like, familiarity with India, as opposed to resentment about India. And you talk very explicitly about kind of blaming India and Hinduism and arranged marriage for why things unfolded in your family the way it did.

So I, I kind of get what you mean. But I guess I'm wondering when you say, "if that makes sense," are you asking that of me because I'm also like, a brown face looking back at you, or because I'm like, a journalist and audio person, and you're anticipating what people in my position might think about those versions they are familiar with, versus the version that you're putting out into the the world right now?

Sopan 24:01

Maybe both. I also think that there's a lot here to chew on. And so I realize, I'm very familiar with it. And I have lived in this world literally my whole life, but also in the course of writing this book. So I'm very familiar with the ins and outs. I'm very familiar with how I feel about it. But I also realize that when you're explaining it to someone, it literally, you're just like, wait, what are you talking about right now? What do you mean that you blamed Hinduism and India? What does that mean? And so I realized, like, okay, to me, in my head, it makes perfect sense. I get it. But when I'm explaining to someone else, I realize okay, but someone else might not. And so I think that's where that comes from.

Sonia 24:35

Yeah, that was something I actually wanted to explore was like, when you say you blame these things, is it because they were the semblances of Indianness that you were exposed to and so, they just kind of became sort of, things to blame, or was it like, the particularities of something about arranged marriage, something about Hinduism?

Sopan 24:53

Both. So, this is by no means universal. You know, not everyone has to deal with this. But like, my parents got married — essentially how that happened is, my dad was already in this country. My mom was living in Canada. My dad put an ad in a newspaper. And then my grandmother on my mom's side answered on her behalf without my mom knowing or having a say in it. And then they were married soon after that. And I never knew the particulars of that. But growing up, I knew they were arranged. When I saw how unhappy they were. And I knew that, at least someone didn't have much say in getting together with them.

Meanwhile, you're watching TV all the time, and these amazing romantic comedies and love stories, you're like, shit, that looks amazing. That's what I want. I can't believe my parents didn't have this. Well, why didn't your parents have this? Oh, it's because you know, they're Bengali, and this is how Bengalis get married. Well, I don't want that. And how could a culture mandate that? Then you have kind of the more stereotypical Indian stuff about like, your parents not caring much about your emotional well-being, it's more strictly about your resume, and strictly about your report card. And that was definitely the case in our household.

Sonia 25:55

Versus me. My mom made fun of me once when I complained about an A-.

Sopan 25:59

Oh, man. Yeah, you had the reverse. Yeah, get out of here!

Sonia 26:02

Yeah, she was like, really funny because it's like, I was always like, really into getting like, straight A's. And I went to Catholic school growing up, and she was like, "Huh, is anybody in the future gonna ask—"

Sopan 26:07

Yeah. So are your parents Hindu?

Sonia 26:12

My — so my family background's very unique. My mom is Catholic. My dad is Hindu, but he's also — he's also a Hindu who prays at a Sikh Gurdwara.

Sopan 26:22

Okay.

Sonia 26:22

My mom's father was Sikh. So the prescribed notion of what we understand "Indian" to be, like, my family totally, like, goes away from that.

Sopan 26:31

Because there's so many different stories.

Sonia 26:33

Yeah.

Sopan 26:34

Like, there's no one way, right.

Sonia 26:36

Exactly. And I think there's a lot more fluidity between cultures and traditions that people don't necessarily talk about —

Sopan 26:41

Especially in 2020. Right. And especially, I think there's a lot less rigidity about it, you know. Basically, there's certain parts of it that repelled me. I don't know what it was like for you when you were young, but like, I couldn't talk about crushes with my parents. You know, I couldn't talk about how much of an outsider I felt like in like my all-white school — mostly white. You know, I couldn't talk to them if I had a bad day with a friend, or if I got bullied or, you know, one of those things. I couldn't talk to them about that stuff.

That's not uniquely a brown problem. First of all, not all brown kids had this problem. And second of all, some white people, some white families go through that, but I ascribed it unfairly to being Indian. Before I was 12, when I was growing up, like in a six to 10 range, we would go to pujas. You know, so there was an Indian community that we were part of. And that was the sense I got from other kids as well. I was like, okay, so this is normal for people that look like me. So I don't want to look like this anymore, because I don't want that for myself. And that's where the rejection came from. Now, over time, you know, I realized as I got older that this was an irrational feeling. It wasn't correct. With the benefit of time, I can say that how you feel about something when you're 14 is not the most rational. It's not the most learned thing. So now, I'm just older now. Now I know differently.

Sonia 28:07

Yeah. Did you have a target audience in mind with this book?

Sopan 28:11

Yes. Anyone who has a relationship with someone that should be better. That was the target audience. I didn't really think about it. I mean, I did for book proposal purposes and whatnot. But for me, I never once wrote it that was about targeting someone. Every single word I wrote was because that's how I want to tell the story.

A lot of authors, I think — and this is, look, if you paint one painting, are you a painter? I don't think so. Am I an author because I wrote one book? I mean, for the purposes of publicity, I'm definitely gonna say yes, but in like two years, you know, I'm not gonna pretend I'm an author. But a lot of authors link their validation of a project to book sales. And, for me, what I've always told myself is, here are the barometers of success for this book. Number one, are you happy with it? Are you satisfied with it? Did this fulfill you? And I can say unequivocally that answer is yes. The second barometer is, if one person picks this book up that does not know you, is not related to you, is a total stranger to you. And reads this book, cover to cover, and tells you that they got something out of it, then that's fine. Everything else is immaterial. So I never once thought about what a target audience would look like.

29:21

Now, I do think that if you have a relationship with someone that should be better, you're going to get a lot out of this book. If you grew up brown in this country, you're gonna get something out of this book, because you will be able to relate to something in the book. You know, if you grew up in a household that was cold, or if you grew up in a household that's really close, you will get something out of this book. Look, I'm gonna pat myself on the back here. If you like storytelling, there are a lot of good stories in here that I'm really proud of in the way that we weave together. When I say we, I mean, Wesley and I. Wesley was very formative in this book. They asked me in the course of writing this book, "Hey, can you send over some comps?"

Sonia 29:53

Comps meaning what?

Sopan 29:54

Comps meaning comparable books. Maybe for publicity purposes or what they can pitch this at, and I had trouble thinking of them. I mean, there are some, obviously.

Sonia 30:03

Like, what ones come to mind?

Sopan 30:06

Well, I'm gonna self-promote here. The Washington Post wrote a piece about books to read in 2020. And they listed my book, and under the headline, "If you like Danny Shapiro's Inheritance, then you're gonna like Sopan Deb's Missed Translations." So there's that. You know, if you read a lot of Jhumpa Lahiri stuff, that, I mean, those are obviously fiction. You see a lot of the same themes, where you see a lot of like, the Bengali world really come to life. I mean, Trevor Noah's Born a Crime. I mean, his book is just marvelous and lovely and funny and so poignant. And we have very, very different stories. But his examines his South African identity. His is based a lot on recall, because it's about him growing up, but it's really a very poignant book and so great.

30:46

The truth is, like, there aren't a lot of books from the South Asian diaspora out there. There are some, but not many. And so I hope that this book gets other people to share their stories. Now, do I personally care about sales for this? I mean, of course you care on some level, but I do have that one person mark. What I don't want is the next like, brown person that has their own story to tell, when they're pitching it. Publishers say, "Well, we tried this with Sopan Deb, and let me tell you, that didn't, that didn't, that didn't work.” I don't want that. But I will say, generally speaking, this was not an easy book to sell. I'm very thankful to Dey Street and HarperCollins for taking a shot on it. But there aren't many stories like this out there. And I hope that one of the end products of this is that people share more of their stories.

Sonia 31:31

I have one more question.

Sopan 31:32

Yeah.

Sonia 31:33

So now, how connected do you feel to your brown side, even though it's not just the side, but the fact that you are brown. Like, I guess, where do you feel the authenticity of what that means now? Is it from getting to know your parents? Is it from just being older? Is it from like, having the space in your mind to think about this? Like, what does that actually mean to you now?

Sopan 32:00

That's a great question. I think — I don't feel as much of a fraud like I used to when I used to walk on the stage at the Big Brown Comedy Show. I feel more connected to it because my parents — because I understand where they came from, and by extension, I now understand where I came from. I still don't love the way my parents got together. I still don't love the way they were towards each other and the way they were towards us, which I think is some — some reflection of cultural values we place on certain things. But, do I feel better about it? Yeah. Am I trying to be white on the inside like I used to, no. This is who I am. And I'm happy with that. Do I have your typical South Asian story like, am I going to have an Indian wedding? Probably not. You know not because I'm anti having an Indian wedding, just because that's not the wedding that Wesley and I want. So, I would say, I feel better. How's that as the answer?

Sonia 32:57

Sounds really good. I mean, like thank you so much for sharing, and just being very open to talking about all of this too, because it is kind of like, I'm being a pseudo therapist, here.

Sopan 33:06

No, this is great. I really enjoyed this conversation. I hope this wasn't a labor for you.

Sonia 33:13

No, this is the occasional but lovable traveling mini pod I'm doing to keep myself going in life.

Sopan 33:19

Yeah, well, I'm happy that I got to cross paths with you.

Sonia 33:21

Okay, great. Thanks so much. So, that's all we have for today of Loitering, the occasional but lovable traveling mini pod I am currently testing a newsletter format. Thanks for listening and have a great day. Goodbye!

* It was actually ONE chocolate sprinkles donut from Dunkin Donuts that we halved, back in January (another lifetime ago). Sopan’s leg is healing well!

Some useful links:

Sopan’s book: Missed Translations: Meeting the Immigrant Parents Who Raised Me

Sopan also recommended Tara Westover’s Educated as another good read.

Emergency Funds for Freelancers, Creatives, Losing Income During Coronavirus (Bay Area-based)

How to deal with uncertainty (thank you to therapist Thien Thanh for sharing)

Learning to Live With Coronavirus, from The New York Times’ The Daily

If you’re looking for a podcast to binge, I recommend Radiolab’s The Other Latif.

Check out what Sopan has been writing at the Times lately.

The best tweet I have seen so far this week.

Share this post