Sonia Paul 00:10

Hello everyone, welcome to Loitering, the occasional but lovable traveling mini pod I am currently testing a newsletter format. And today I am not traveling but loitering on Zoom with a very special guest. Can you please introduce yourself?

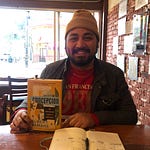

Eva Holland 00:25

Hi, I'm Eva Holland. I'm a freelance writer. I live in the Yukon Territory in northern Canada. And I have my first book just out. It's called Nerve: Adventures in the Science of Fear.

Sonia 00:35

Great, and so for people are kind of unfamiliar, what is the Yukon? Can you talk about where that is, exactly, and what kind of environment surrounds it?

Eva 00:45

Sure. So the Yukon is one of three Canadian territories. We fill the northern part of the country. And basically, we're a territory rather than a province, so we have fewer sort of regional powers, like in terms of devolution of powers from the federal government. Provinces have less than American states do, and territories have less than provinces. And we are north of British Columbia and just east of Alaska. So we're kind of a little triangle there next door to Alaska. The Yukon is about the size of California, but with 35,000 people instead of 35 million. So it's pretty empty. It's a sub-Arctic, primarily, the very northernmost part of the territory is north of the Arctic Circle. So it's, you know, forests and mountains and rivers and lakes and bears and caribou and all that good stuff. And it's where the Klondike Gold Rush took place. And we still have a lot of mining here and tourism when there's not a pandemic. It's a pretty cool place.

Sonia 01:44

Okay, that's really interesting. This is a good segue for a question I had was that you kind of live in the wild, I think. Of course, maybe you might not realize that or other people around you might not realize that, but I think compared to a lot of people who live in cities and more urban environments, you're in a place that is pretty out in the open. And I found it very interesting because I know some people who might think that sort of environment might be a very scary place to live in. And I was curious how you would describe your relationship with your environment and whether or not there's any fear in being in that sort of environment, especially when you consider things like isolation and the availability of different resources.

Eva 02:29

Yeah, I mean, it's all relative, right? By Yukon standards, Whitehorse, the capital city, quote, unquote, where I live, is the big town right? And we have three Starbucks and kind of have a lot of creature comforts compared to some more remote communities. But on the other hand, like we get grizzly bears coming into town sometimes and moose and stuff, so it is pretty wild. But, I used to find places like this scary when I was younger and was more of a city kid and had less experience. I felt safer in cities, just sort of safety in numbers kind of ways. That isolation can feel really vulnerable. But I have changed my perspective on that, I think. I mean, there's still — your imagination is gonna run wild. There's a reason why tons of horror movies take place in like, a cabin in the woods or something. But as I've gotten to know, this community, I've been here for just over 10 years, my perceptions of what's safe, or I guess my comfort zone in different scenarios, has really changed in that time. And now I feel pretty safe in wilderness settings, and certainly in this community.

Sonia 03:22

Yeah, so there's safety in a physical environment, but your book is more so about different emotions that you're trying to tackle. And then you have this line that I think is just kind of pretty emblematic of like, your mission with this book, is that it says, "I've sometimes felt as though my life is less a pursuit of happiness, and more an ongoing endless duel with fear." So, can you just expand upon that and what exactly you're trying to talk about here?

Eva 03:50

I, I guess I've — and I know that this squares strangely sometimes for people who follow my writing was sort of my professional persona or some of the stuff I've written about done for work — but I've always felt like a pretty cautious person, pretty risk-averse, scared of lots of things. And particularly since I moved here 10 years ago and have been trying to learn all this wilderness adventure travel stuff, I'm always less experienced than everyone I'm going out and about with, and I'm always the most scared. So I think I really internalized that role of sort of the token scaredy-cat in the group. And there's been a process of sort of coming to terms with that and being like, it's okay to be a beginner, it's okay to learn things. It's okay to be nervous. But, it's also not a fun role to be in, and I was getting tired of the extent to which I felt like fear was hemming me in and making my life smaller, I guess, than I wanted it to be. So I decided that I wanted to change that dynamic.

Sonia 04:44

And you did so in the form of a book.

Eva 04:47

Yeah.

Sonia 04:48

And so, do you think you would have done this had you not written a book? Like, what was the process of doing it as a writer, and how does that relate to you actually doing it. Like what do you have done it any other way?

Eva 05:01

I think I would have done some of it, even if I wasn't writing about it. It did start as a personal project, specifically, the thread of my fear of heights and wanting to overcome my fear of heights was something that I took on as a personal project before I decided to write about it. I don't know if I hadn't had a book contract to fulfill, if I would have stuck to it as persistently or been as willing to put money into things like therapy for trauma or phobias. So I don't know that I would have been as successful as I ultimately was, spoiler alert, in changing some of the dynamics of my relationship with fear if I hadn't been doing the book. And this is part of that, I guess, split persona that I referred to earlier — I've always been more driven when I have to write about something. I'm always more willing to push myself, push my boundaries, do something scary if I have to come up with a story about it and get paid. And so, doing it as a book really meant that I would see it through. I don't know that I would have stuck to it when things got hard otherwise.

Sonia 05:54

How much is it that money has to do with that versus other people just know you're doing it?

Eva Holland 06:00

Hmm, that's a good question. A bit of both, I think. But yeah, the money piece is real. I'm not somebody who spends a lot of money on self-improvement type of stuff. And not that I spent a ton of money on, for instance, the therapy that I did to resolve the trauma from my car accidents, I think I ultimately spent maybe four or $500 on those four sessions. I can't remember, I'd have to check it out. But it wasn't outrageous. Certainly, the value to now no longer be having panic attacks and flashbacks when I'm driving is enormous. But I don't know if I would have invested that money if I didn't see it as sort of a professional investment, rather than a personal one, which is kind of dysfunctional now that I think about it.

Sonia 06:37

Oh, you tell me, a couple of friends and I are currently going through a book together that is kind of like, a self-improvement type book. And we had to write work views and life views. And it was really interesting to talk about the differences between the two among us — but let's just backtrack for the audience.

So the fears that you talked about in your book or your fear of heights, you're sort of anxiety around driving cars or getting into car accidents, and then also this fear of loss, with losing your mother. And at one point in your book, I remember you remarking that you didn't even realize that some of these fears were actually fears until you verbalized them. And I was wondering like, what is the role of verbalizing or actualizing something out into the world, in this whole relationship with fear. Because you also talk about like, fear that's internal versus fear that's external.

Eva 07:31

I think it's important to name it. And I don't think you can really, at least I couldn't, speaking for myself, understand what was happening to me until I named it until I recognized a pattern and said, "Oh, I'm afraid of heights." It's not just that I happen to sometimes have panic attacks when I'm exposed to heights. It's that there's something consistent happening here. And the same thing with the others. I mean, the fear of losing my mom was something that had been with me for a long time, but it was helpful after she died, I think, to confront whether or not that fear was now mutating into a fear of people around dying more generally. And it was helpful to name what was happening with these car accidents that I'd had and the flashbacks.

08:06

You don't always notice right away. Sometimes it takes someone external to you. The prologue of the book opens with me having a pretty serious breakdown partway up a mountain, basically, on an ice climbing trip. And I told that story to my oldest friend a few months after it happened. And I said, I don't know what happened, I just freaked out. And she looked at me like I was kind of like, really missing something obvious. And she was like, "Eva, that was a panic attack." And I was kind of like, "Well, I don't have panic attacks. Like, that's not something that happens to me. But it is, it can be, right? You can't really address a problem or decide whether it's even is a problem until you've named it for what it is and identified the role that it's playing in your life.

Sonia 08:43

What happens when maybe certain people around you try to undermine what is actually like a legitimate fear for you? That's like a sort of another idea that you kind of got at is that — Are my fears just silly? Like, how rational are they? Like you have this example in your book where you thought you were being stalked by someone, and it turned out this person's actually stalking a lot of different people, calling up numbers in the phone book, and then you felt like so silly afterward, like who would just call the cops about like these one-off phone calls? And so, like, how do you grapple with naming fears that maybe in society or culturally speaking, it may not seem as scary to other people?

Eva 09:26

Yeah, it's hard. Shame and embarrassment is such a part of this puzzle for everyone, I think. Certainly, it was for me. I felt really lucky here in that the people that mattered, the people that were close to me, didn't question the authenticity of what was happening to me. They didn't make fun of me. Probably that was because my fears were so close to the surface that most of them had seen me cry or hyperventilate or have some sort of panic. And so they knew it was real because they'd seen it happen. They'd seen me go from like, rational, happy, competent person, to like, crying on the ground. The incident with the guy that I thought was stalking me — it would have been a different story if it was people in my life saying you're blown out of proportion. But it was, you know, it was internet commenters in the local paper. And so it upset me and made me feel foolish. And it made me question myself, but not to the extent that if I had been undermined by people that I cared about, I think. But yeah, no, I mean, the public-facing piece of it is so hard. My panic was always worse if I had an audience, and it was extra worse if I had an audience of strangers or people that I didn't assume would be sympathetic. So there were things I would try with my close friends around who I knew it would be okay, if I cried or whatever that I wouldn't do if I thought there might be more variables in terms of who might see me.

Sonia 10:40

Yeah, and then you talk a lot in the book about the distinctions between fear and anxiety and trauma. And I go through this situation, not just with these words, but other words that then make me second guess like what are the actual definitions? What are we really trying to say when we say these words? And I was wondering if you can help us — me — parse out the distinctions between fear and anxiety and trauma? Because it sounds like they're like, cousins, almost, as opposed to like direct siblings, if that makes sense.

Eva 11:14

I think there's a limit to how finely we can parse those distinctions. I did try. But what I found when I tried is that if you push too hard on those distinctions, they fall apart under pressure. So there's a utility to making a distinction to a certain point. You know, the sort of official distinction between fear and anxiety is that fear is present when you perceive an objective threat. A clear and present threat to your safety. And anxiety is about a perceived threat or a more amorphous threat or a potential threat or an imagined threat. And so you could say that like, a bear in your campsite. That's fear, because that's a threat. And lying awake at night worrying about a bear in your campsite, even if there is no bear in your campsite would be anxiety. And then anxiety to a point of sort of being unreasonable or — maladaptive is the term that neuroscientists use — would be lying awake at night worrying about a bear in your campsite when you're not even in bear country.

So there's like, there's this kind of gradations of how we react to threat and the possibility of threat. But they do come apart pretty quickly. Because, you know, you don't always know if there's a bear or not. If you're in bear country, what's a legitimate fear versus an anxiety gets harder to say, because you don't know what's around the next corner. So, it's tricky. A woman that I quote in the book gave the examples of the hydrogen bomb and the terrorist as clear and present threats that prompt fear as opposed to anxiety. But I can't think of two better examples of things that induce anxiety even when they're not present, when they're hypothetical. The atom bomb was a symbol of dread and fear and potential threat for people all over the world for decades. It didn't have to be present. There didn't have to be a possibility of a launch for people to feel that way. And, you know, I mean, people have written books on the idea of the terrorist in our minds. So it's tricky, and I do you think there's some utility in trying to make those distinctions, partly in terms of managing your own response. Like, to say to yourself, okay, is this a real threat right now? Or is this in my head? That can be useful. But we hit our limits pretty quickly, I think, because they are all closely related. It's a spectrum, I guess.

Sonia 13:15

Yeah. And now, of course, we have this thing that is both clear and present in front of us, or also like, hypothetically, in front of us. COVID-19. And it was wondering how the emergence of this pandemic has adjusted your thoughts on these topics, if at all.

Eva 13:35

It's kind of the perfect example, right? Maybe even better than the bomb. It's a literal threat to many people right now. And it's a potential literal threat to all of us. But in the meantime, for a lot of us, it's an ambiguous threat. You know, if you're sitting in a community that it hasn't reached yet. Doesn't mean you're not afraid, but it's not a threat to you yet, at least not as a physical medical threat. It might be a threat to your economic situation already. So it's a perfect example of how complicated this threat assessment thing is, objective versus subjective versus theoretical or imagined threat. It's interesting to have this sort of dramatic example of how all this stuff works for me to kind of put in the context of my research.

Sonia 14:14

It seemed to me in reading that there's a very strong relationship between fear, agency, discomfort and control. And what is your sense of that?

Eva 14:26

I think that's very perceptive. Yeah, agency and control. You know, one of the most fascinating things to me that I learned is that even the illusion of control can protect you from fear. You know, until the illusion runs out. If you think you have control of a situation, then that can buffer you against fear. You know, none of us like losing control, particularly in a potentially dangerous situation. That's when fear starts to creep in, is when we no longer feel like we can control the variables around us, to find our way out of danger. And that's something that trauma researchers have learned. You know, they're still trying to understand why some people are more traumatized by the same event than others. But one thing that they think is part of it is if you have a sense of agency, if you feel that you can save yourself, or that you did save yourself from the situation. Then that protects your mind from traumatic memories after the fact.

Sonia 15:17

Yeah, and I mean, your friend’s situation that you write about in the book where she was chased on her bicycle, like, would you mind talking about that? And maybe we can just use that as an example to figure this agency situation out?

Eva 15:33

Sure. So I have a friend from back when I was younger, who, a number of years ago was biking on a bike path in kind of a suburban area, and she was approached by this man who suggested that they ride together. And she got a weird vibe from him, and she declined to ride with him and went back the way she came. And all of a sudden, he appeared behind her, biking really hard, right on her tail, right off her rear wheel. And she didn't understand what he was doing or why, you know. But she had this huge spike of fear. And she swore at him and swerved away and then biked away really fast. And she immediately, immediately felt sort of the regret and the second-guessing of, you know, was he just being playful? Or did he want to race? Like, what was he doing? And why was I so rude? And she actually yelled out, "I'm sorry, you just scared me," back down the bike path after she was out of sight. And he killed the next girl who came along, it turned out.

So she ended up being, you know, a witness, and he was eventually convicted for murder of basically the next young woman to come along that day on the bike path. And that's like, one of the craziest stories I've ever heard. And I was really grateful she gave me permission to put it in the book. Because I think it really demonstrates — one, the power of fear to help us survive, if you listen to it and override the sort of politeness default that we have, even when we know something is wrong. And two, she didn't have trauma from that incident. She had sadness and anger, and a certain amount of survivor's guilt that passed with time. But she didn't end up feeling like she nearly died because she got herself out of it. And so, what she came away with was sort of a sense of agency and a sense of faith in her own ability to look after herself, as opposed to an undermining of her ability.

Sonia 17:17

Yeah, when I read that, I thought it was so profound, actually. I mean, I remember talking about this with another author who's written about women and crime and their relationship with crime, but this idea of like victimization mentality, and I think there's a tendency for a lot of people to grab onto that as well, when they go through something incredibly traumatic. And yeah, and it sounds like too, I mean, a lot of how people cope with all that could go wrong, or is legitimately scary in their lives, is also a personal journey, but it's a personal journey that's wrapped up in science, as you've written about.

17:58

And so I was wondering if you can maybe talk about some of the, quote-unquote, solutions you tried to figure out how to negotiate your fear with, say, heights or the car accidents or your mom's loss.

Eva 18:14

I think EMDR is the perfect example for what we're talking about here in terms of agency and how we sort of tell ourselves the story of what happened to us. So EMDR is a therapy that I underwent to try to resolve these flashbacks and sort of feelings of doom and panic that I was having while driving after having a series of serious car accidents. It stands for eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. It's a trauma therapy that was developed in the late 80s and early 90s. Basically, a trained therapist prompts you to move your eyes back and forth in a rhythm. They have different methods of doing that, I use these sort of buzzing pods. And they have you tell the story of what happened to you. And then, as you're telling the story, and your eyes are moving back and forth, they lead you through a series of questions about how you feel, how your body feels, if you feel tightness in your chest, if you feel — you know, your mouth downturned like you're about to cry, this sort of thing. And then you keep doing these sessions with these sets of eye movements while you focus in on these feelings, and then they seem to sort of dissolve. And somehow at the end of it, the intrusive memories that you're having from your traumatic event are no longer intrusive. You can still remember them. But they don't jump in and grab your brain anymore, for lack of a better description.

So I did EMDR to try to stop, you know, crying and pictured my own death when I was driving, basically. And agency was a big part of it. One of the things that we talked about with my therapist was — so I had two rollovers in winter conditions within four months of each other one winter. And the first one, I spun out on black ice on the highway. And I was spinning in my SUV across the highway, and I was like, this is fine. I'm gonna hit that big snowbank on the far side and I'm gonna come to a stop. This is okay. I'm spinning but there's no traffic, everything's fine. Back to that illusory sense of control, right? And then I hit the snowbank and flipped over it rolled into the ditch, but I didn't anticipate that. Whereas the next accident, partly because of the previous one — I hit a big patch of hail in a hailstorm, and I lost traction and I was fishtailing down the highway. And I knew what was coming, and I couldn't stop it. I was sitting there and especially in the car freaking out until I again rolled into the ditch. And the trauma from the second accident was way worse than the first. And what the therapist made me understand is that part of that was because of my fear and my awareness of my own lack of control. So that was really interesting to learn for me, a sort of a light bulb moment.

And then one of the things that we did in therapy is we sort of reframed the story that I told myself about these accidents. And where the story had been, "I'm incompetent, I'm terrible, I'm going to die next time. Maybe I should die." You know. We reframed it to, "I've been unlucky. I'm a good driver. Nobody could have prevented that," or you know, different kind of takeaways, trying to reframe my understanding of what happened to take away sort of the self-defeating and critical part of my mind that was sort of beating myself up over this. It was really interesting. And it taught me a lot about — yeah, agency and control, and how powerful it is to think we know what's happening, even when we don't. Our capacity for sort of self-deception is actually really important. It can protect you, which is sort of weird. So often we talk about kind of radical honesty or wanting to be really self-aware, but sometimes it's good to not know that you're in deep shit, you know? If you can't fix it.

Sonia 21:22

Yeah, but how does the actual mechanism of flicking your eyeballs work to calm the nerves or just quell the fear?

Eva 21:32

Yeah, they're still trying to figure that out. And people were really skeptical about this therapy in the 90s. And they've come to accept it. It's now quite widespread because it keeps working better than the placebo effect, and better than some of the other trauma therapies that we have for some people. But they don't understand the mechanism at all. They do know they have isolated the eye movements in clinical trials. And if you take them away, and it's essentially just talk therapy, it doesn't work. They have straws to grasp at, you know, we understand that, you know, REM sleep is related to our memory storage processes. So something about eye movement may be connected to memory. They have documented changes in people's brains before and after EMDR in terms of sort of, like, a density of gray matter and this sort of thing. There's a ton of studies underway to try to pinpoint this mechanism, but they really don't know why it works. They just know that it does for some people, for more people than not, I think.

Sonia 22:24

Wow, yeah. And I also kind of just want to touch on the topic of avoidance. Because, you know, I feel like we get mixed messages about fear. I mean, why should people put themselves through stressful situations that make them fearful or anxious versus this whole sort of other message of "it's time to face your fear?" And choose that, even though the struggle of facing your fear is a struggle as opposed to joy. And so, how should we figure out an approach to fear when culturally, there are these disparate ways? And if we can't rely on like a cultural indicator, what is the like, strongest scientific indicator for how we should approach our fear?

Eva 23:11

Hmm. Yeah, I mean, that's something that I only really touch lightly on in the book, but I wrestle with a lot is when is avoidance, okay, basically. And I think — it really depends on the level of sort of impairment that you're experiencing in your life. If the thing that you fear is quite tightly focused, you know, quite a narrow fear and it's not bleeding out into your life, then maybe it's not worth the pain of confronting it. Because this stuff is hard, right? It's hard, it can be expensive. So for instance, I write about a woman in the book who was afraid of mice. To the point where she was terrorized by it. She couldn't put her feet on the floor in a dark room because she was so afraid. So I think if you're afraid of mice, and your home is mouse-free, and you only have a panic if you see a mouse and you never see mice, then that's okay. Maybe you don't need to address that fear of mice.

But if you are being terrorized by imagined mice even when there are no mice present — like, one of the definitions of addiction, right, is if it's affecting your work life or your family life or sort of impairing you in some way beyond the actual effect of the substance. If it's bleeding out into your life in harmful ways, and I think that phobias or fears more generally, I think a similar bar is useful of like, is this impairing you in meaningful ways? And if not, then maybe you just let it ride. You know, like, if you're afraid of sharks, but you don't live near the ocean, and you can still enjoy a beach vacation once a year, then great. If you're afraid of sharks, and it means you can't get in the bathtub, then maybe you want to take action, right? I mean, everybody has to make their own call, but I think that's probably a useful guideline.

Sonia 24:42

Yeah. And also, now that you finish this book, do you think you're a less fearful person? Like, is it also because maybe you're "out" with your fear that the fear is not as big? How do you feel about all that?

Eva 24:59

I do think I'm a less fearful person now than I was before I started on the book, which was not an outcome I anticipated. It certainly was not something I promised in my book proposal, like, I'm gonna sort this shit out. You know, I didn't expect that necessarily. But I am less fearful now. I am also less embarrassed about being afraid when I am afraid. So that's also helpful progress. You know, I'd say I have a healthier relationship overall with fear. The aspects of my fears that were really kind of irrational and that were impairing my life because they were so exaggerated, I've made some real progress on resolving. And where I have fears otherwise, because of course, I still have lots of fears — I have a healthy relationship to accepting them, understanding them, and not maybe overreacting to them. But not expecting to live a life free of fear by any means.

Sonia 25:44

Yeah. How do you think your online presence has maybe like, confused or assisted your relationship with fear? Because you talk a little bit about like, people wouldn't consider you to be a fearful person because you're kind of out there, you have a large social media presence. I mean, you live out in the Yukon, and you do pretty adventurous reporting. And so I was wondering if you have any thoughts on that at all?

Eva 26:14

Yes, it's funny, I shouldn't have looked, but I looked at Goodreads earlier today. And I saw, like, a review from someone who liked the book generally, but her one hang-up was she was kind of like, "This person claims to be fearful, and like, look at her life. She's not fearful." And I don't really know what to say to that, because fear isn't necessarily about what you see on the outside, right? People can be terrified and you might not know. There's fear of the emotion that we feel inside. And then there's how we react to those fears on the outside. And, I mean, I get, I get the skepticism. I have a friend who has been kind of my rock climbing teacher who told me he was afraid of heights too. And I was like, "No, you're not. Like, I've seen you climb, you never seem scared." He's like, "Well, I just keep it on the inside. I'm scared every single time." But I guess, I'd say it's really about how we experience these things internally. And, I don't know, the trip with memoir, especially one that's as driven by memory and sort of internal emotional states as the sections of memoir in this book are, is that, you just have to trust me, I guess, that I really was terrified. Yeah, no, it's a funny thing.

Sonia 27:13

Well, yeah, I mean, and I totally — I think it's very legitimate for someone like you to actually have these fears. And it's kind of like, well, who do you know, you only know, like an online presence. But then, I guess maybe the broader idea my question was touching at is that so much of our lives, especially now, you know, we're all online. We're all on Zoom. It is a performance. And so how much does performance sort of like, shape fear or our way of coping with fear, if at all? I don't know if that's just like me meandering in my thoughts, but...

Eva 27:47

No, I think I see what you mean. And I have found some relief, I guess, in having this book out there. Because now I don't have to keep up any kind of performance. You know, like, I didn't advertise the fact that I was afraid of heights if I told an editor that I would do a story for them that involves going up a mountain. You know, like, I didn't want them to know that I had like, a limitation there that might affect the story. And so, it's kind of freeing to just be like, "Here's all the stuff I'm afraid of. And to not be embarrassed or to try to hide it and paper it over with some sort of facade of bravery is kind of a relief. And so I don't know, yeah.

Sonia 28:24

What is the most useful thing you learn throughout the course of reporting and writing your book that you think listeners of this podcast or readers of the Q&A format to the podcast would find nice during this time of shelter in place and the pandemic?

Eva 28:43

I think the most useful thing was not any of the stuff I learned about how to control or overcome fear, but was really what I learned about the necessity of fear. You know, fear is a survival tool. It's an instinct that we have to keep us alive. And learning to kind of come to terms with that, and to accept that fear has a really vital role to play in my life really helped me be more at peace with the fears that I do still have and with the fact that I will be afraid of things in future. You know, letting go of some of that shame and the desire to fix it, and to just say, "Okay, it's okay to be scared." In fact, it's really important and a good thing to be scared in some ways, because it keeps us alive. That was helpful for me. It's something I've been thinking about during this time, because it's so easy to be really hard on ourselves about fear and anxiety and dread and to think, "Oh, you know, I'm sitting here freaking out, and I'm not, you know, intubating people in an ICU. I'm just sitting at home being scared." Like, it's really easy to beat yourself up about this stuff, but it's okay. It's important to feel afraid right now, actually, you know.

Sonia 29:44

Thank you so much for making the time to talk with me and talk about these ideas. I really appreciate that.

Eva Holland 29:52

Thanks. That was great. That was really fun.

Sonia Paul 29:54

So, that's all we have for today of Loitering, the occasional but lovable traveling mini pod I'm currently testing a newsletter format. Thank you for listening and have a great day. Goodbye!

Some links to listen, read, watch:

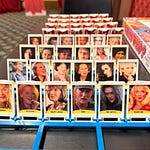

Nerve: Adventures in the Science of Fear, by Eva Holland

Also by Eva: The Frontier Couple Who Chose Death Over Life Apart; and Saving Baby Boy Green (on the future of neonatal medicine)

If you’re looking for a podcast to binge, I highly recommend Floodlines, from The Atlantic

If you like to think about (or at least want to consider), the parallels between physical and emotional endurance: To Run My Best Marathon at Age 44, I had to Outrun My Past, by Nicholas Thompson

Anatomy of an internet shutdown, by Jina Moore (for the new news site Rest of World, about the influence of technology around the world)

I Was Depressed Before All of This. Now What?, by Elizabeth Flock (whom you might remember from Loitering by the River)

Even my mom called to ask me if I was watching the PBS series on Asian Americans (I am!), and it’s worth watching, especially now given rising xenophobia against Asians (see this for one of the most glaring examples)

My Restaurant Was My Life For 20 Years. Does the World Need It Anymore?, by Gabrielle Hamilton

The Coronavirus is Rewriting Our Imaginations, by Kim Stanley Robinson

Share this post